Arizona Daily Star

May 17, 2009

Photos by Benjie Sanders / Arizona Daily Star

Desert druid writes on (original)

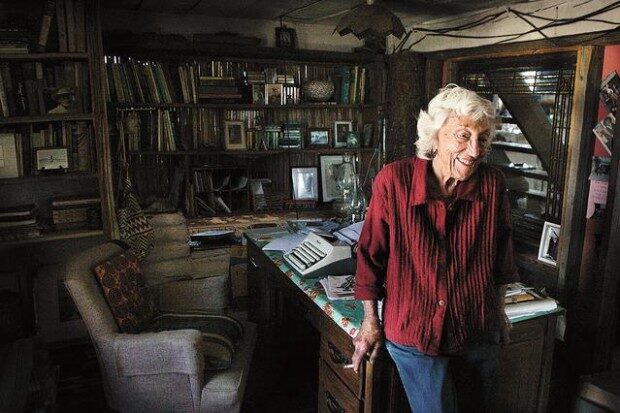

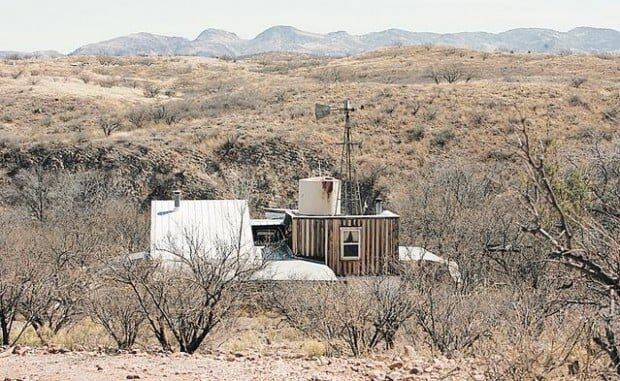

It’s five miles of rutted, rocky road to Byrd Baylor’s house and worth every bone-jarring dip. At its end stands the acclaimed children’s author, rail-thin, wearing jeans, a long-sleeve shirt and silver earrings. In her driveway sits her well-mudded Nissan pickup, plastered with several stickers, among them one reading: “A tree-hugging dirt worshipper.” Her house of adobe, which friends helped her build more than 25 years ago, nestles into 35 acres down Arivaca way, about 50 miles south of Tucson.

It has a tin roof, tree-trunk posts and a windmill that hasn’t worked in years. Instead, there’s a generator amping up the little power that does get used.

Baylor gets her news from a portable radio, and friends regularly drop off three days’ worth of The New York Times, along with the Sunday Arizona Daily Star, at a cafe in Arivaca, about six miles away.

She types out her books — 30 or so at last count — on one of three manual typewriters, then turns in the manuscripts to her accommodating publisher.

“A laptop is too much technology,” says Baylor, 85. “I’m a slow worker. I love the process of writing. It’s a pleasure because at some point you will find a line you really like.”

Right now she’s working on a collection of essays, “True Confessions of a Desert Druid” — autobiographical pieces dealing with “the insanity” of her life.

“I always knew I was going to be a writer,” says Baylor. “When I was a little kid, I was sending off poems to magazines and signing them, ‘Byrd Baylor, age 36.’ “

Born in San Antonio, Baylor is related to the family namesake of Baylor University. Her first name comes courtesy of her mother’s maiden name. “My mother was a Byrd, she was related to Admiral Byrd. It’s an endless thing.”

Her father, a self-taught geologist, wound up running a gold mine in Sonora “when I was a little kid,” says Baylor.

By the time she was school age, the family was living in Tucson, though vacations were often spent in mining country.

Later, Baylor studied creative writing at the University of Arizona. In her junior year she married a naval ensign assigned during World War II to Bear Down Gym, then a temporary naval dormitory. The newlyweds moved to San Francisco, but the marriage did not last. Baylor returned to Tucson and landed a job with the Tucson Citizen.

“I was hired as a reporter and was supposed to do rewrite. At some time I started doing these little features. They liked those, so they let me do more.”

She wrote about people on the reservation. She wrote about poverty in Tucson. But when she started to write about a well-known Tucsonan who also happened to be a slumlord, “I was cut off absolutely. I was so innocent at the time.”

George Rosenberg, former managing editor at the Citizen and a “fond admirer” of Baylor, says, “Byrd was a wonderful, elegant writer. She was just too good for the trouble and culture of a newsroom. Obviously, her world was different.”

In her Citizen days, Baylor had remarried, this time to Star newspaperman Dick Schweitzer, but that marriage, too, would not survive.

Meanwhile, her first children’s book, “Amigo,” was published in 1963. “That first one was in rhyme. It was about a prairie dog. The publisher asked me if I would make it a squirrel. I said no.”

Her books, she says, reflect “all the things I love. I love the land, the animals.” Inspiration comes from the daily treks she takes in the desert. “I have learned so much by walking or just sitting on a rock.”

The downtrodden have also served as grist for her writings. “After I left the Citizen I joined with a few people who wanted to be of help,” says Baylor, who counseled people from the Tohono O’odham Reservation who had moved to Tucson.

“The first person I went to see was put out of her house, and the house had been condemned by the county Health Department. They were sleeping in the backyard. My first day on the job, I took six people home with me. So, no, I was not a great social worker.” Even so, the experience served as springboard. “That was the beginning of my novel, ‘Yes Is Better Than No.’ “

Her only novel, it focuses on the experiences of a poor Tohono O’odham family, and was written while Baylor was working for the late Tom Bahti at his Indian arts store.

“My father put up a sign in the store that said, ‘If you don’t see what you’re looking for, please ask. Otherwise don’t disturb the clerk on duty. She’s writing a novel,’ ” remembers Mark Bahti, Tom’s son. Tom Bahti also illustrated two of Baylor’s books.

Baylor has a son, Baylor Stanley. Another son, Tony Stanley, is deceased, but she has three grandchildren from Tony.

Last summer she was diagnosed with cancer in her stomach lining. “I spent three weeks in the hospital, had surgery and then the chemo, but I blew off the last chemo.

“I was having a nutritional problem,” says Baylor, a vegetarian who now supplements her diet with vitamin B-12 and gets regular blood tests. “I feel fine,” she says.

While most of her writings have been classified as children’s books, several, says Baylor, have appeared in adult magazines.

In March, Baylor was honored with a “Local Genius” award by the Tucson Museum of Contemporary Art for her work not only in the literary world but as a naturalist and humanitarian.

“She’s an example of an artist who’s living and creating work on her own terms. There’s no distinction between the life she lives and the work she does, and because of that her work is exceptionally honest and original,” says Lissa Gibbs, former associate director at the museum who was involved in the nominating process.

Many of Baylor’s stories have been translated into other languages, including Chinese and Japanese.

“A Japanese man had heard ‘Everybody Needs a Rock’ in Japanese as a little kid. He decided he wanted to come and see America and see a coyote and see me. I’m not sure in what order.

“He went to the Grand Canyon first and talked to someone at the gift shop about me. That person drew a circle around Arivaca. He showed up here on a bicycle. I happened to be here. He was just a beautiful person.”

And perhaps the genesis for yet another Byrd Baylor story.

A home just perfect for writing (original)

Byrd Baylor’s adobe house near Arivaca is about as close as one could get to a writer’s getaway.

With no television and no traffic to speak of, there’s little to distract, save for the rattlesnakes that occasionally slither inside.

“I don’t kill anything,” says Baylor, who sold her house in Tucson and bought the property in the early ’80s.

Why here, she isn’t sure, other than she’d “been out here as a kid” while her father was looking for gold.

When the man she’d given money to build her home took off, she turned to friends and family who helped build the house, which features vigas from Mount Lemmon, some saguaro-ribbed ceilings, a fireplace and three wood-burning stoves.

One of the people who helped build her house was a man walking in from Mexico, just a few miles to the south.

“He asked for a job. We told him nobody was being paid. But he still picked up an adobe and started working. He loved doing that.”

Water from her kitchen sink and shower runs outside, irrigating the trees. The kitchen holds a wood-cooking stove and a refrigerator that runs on propane.

She has a composting toilet and a shower whose windows look out to the desert. She heats water for her shower with a wood-burning water heater.

A wood-burning stove also heats up her office, tucked beneath her sleeping loft. “A pipe from that stove goes up to the loft,” says Baylor. “It’s one cozy place.”

Come warm weather, she retreats to a covered porch out back, furnished with a real bed. “I sleep out here all summer,” she says. There’s also a hammock on the side porch, as well as a solarium filled with plants on a back porch that was added later.

Concrete now covers the home’s original dirt floors. “I had them for seven years and I truly loved them. But it requires some work. You have to be willing to sprinkle and sweep every day.”

She has a generator and a “little bit of solar,” but she lights her nights with “more oil lamps than anything.”

Here she has made her home for more than a quarter century. And while she is welcoming to visitors, not all can find her.

“I gave a conference in Boston. Some people from there went to the U of A and wanted to look me up. They got to the store in Arivaca and they drew them a map. They came part of the way and turned around. They said nobody could live this far out.”

Byrd is ‘model of hospitality’ to border crossers’ helpers (original)

As I drive up to Byrd Baylor’s house near Arivaca, a red pickup truck with four young volunteers pulls up beside me.

They are members of No More Deaths, the Tucson-based organization that offers humanitarian aid to border crossers from Mexico.

For the last five years they’ve set up camp on property owned by Baylor 11 miles from the border — in an area heavily traversed by illegal immigrants.

The volunteers “keep medical supplies and water there. And from there they hike into the hills, pick up water bottles, et cetera,” says Baylor.

“It’s lovely to have the support of people like Byrd,” says volunteer Danielle Alvarado, a teaching assistant for the Tucson Unified School District. “We drive by here every single day, and sometimes we step in. Byrd is the model of hospitality.”

“They move differently now. They’re going down canyons or they’re going way out on the reservation. It’s more treacherous that way. They get hurt.”

However, people do come to her house at times. She talks about a woman, about 40, and her nephew, about 20, who showed up at her door one day.

“The woman had severe cramps and was dehydrated. I gave her a couple of teaspoons of water. I had her lying down. The nephew said he wanted to turn themselves in, so I called the Border Patrol. I asked them to come and get her, that she needed medication.”

After being asked where the woman was, Baylor answered that the woman was in her home. “He said I was harboring her. I said, ‘I’ll quit harboring her when you come to get her.’ I kept calling. Nobody came. After five hours they came.”

Rob Daniels, spokesman for the Tucson Sector of the U.S. Border Patrol, says, “We don’t want to give an indication you can’t give someone something to eat or drink, especially if they’re in distress.” The main distinction, he adds, is that “you’re not furthering entry into the U.S. We always encourage people to call us.”

Some of the Border Patrol’s heaviest activity, he adds, occurs north of the border and west of Interstate 19 — right in the area where Baylor lives.

Byrd Baylor has been interviewed by National Public Radio several times regarding border issues.